South Africa’s long wait for justice over apartheid crimes

Lukhanyo Calata’s earliest memory of his father is his funeral. He remembers the cold, and his mother wracked with grief. It was the winter of 1985, in the small South African town of Cradock in the Eastern Cape.

He recalls feeling as if the ground was moving beneath him as it reverberated with the toyi-toying – stomping and chanting – of thousands of mourners.

They had come from all over the country to pay their respects to Lukhanyo’s father, Fort Calata, and three other young men who would come to be known as the Cradock Four.

Despite being one of the apartheid era’s most notorious crimes, the alleged perpetrators have never been taken to court even though they were not given amnesty by the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

But now a push to reopen investigations into this, and hundreds of other crimes from the racist apartheid era, is gathering momentum.

The 1985 murder of the Cradock Four sparked outrage across the country.

The president of the then-banned African National Congress (ANC), Oliver Tambo, addressed the masses attending the political burial through a message sent from exile.

That day, President PW Botha announced a state of emergency in the Eastern Cape, extending it nationwide the following year. The measure gave the police and security forces sweeping powers to crack down on activities demanding an end to white-minority rule.

As a rural organiser for the United Democratic Front (UDF), a prominent umbrella organisation of hundreds of groups fighting racial segregation, one of the four, Matthew Goniwe would sometimes travel to the city of Port Elizabeth for meetings. For one such trip on 27 June, he was accompanied by Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli.

The four community leaders were known to the police for their anti-apartheid activities. As they made the 200km- (125 mile) drive back to Cradock that night, they were intercepted by a police roadblock.

Their burnt bodies were later found at separate locations.

The government at first denied any involvement in their deaths and a 1987 inquest found that the four men were killed by “unknown persons”.

But a second inquiry was opened at the tail-end of white-minority rule in 1993, after a newspaper reported that a secret military signal had been sent calling for the “permanent removal from society” of Mr Goniwe, his cousin Mbulelo Goniwe and Mr Calata.

It concluded that security forces were responsible for their deaths but did not name any individuals.

Justice pending

Lukhanyo Calata was three years old when his father was killed. Thirty-eight years later, the families of the Cradock Four are still waiting for the perpetrators to be held accountable.

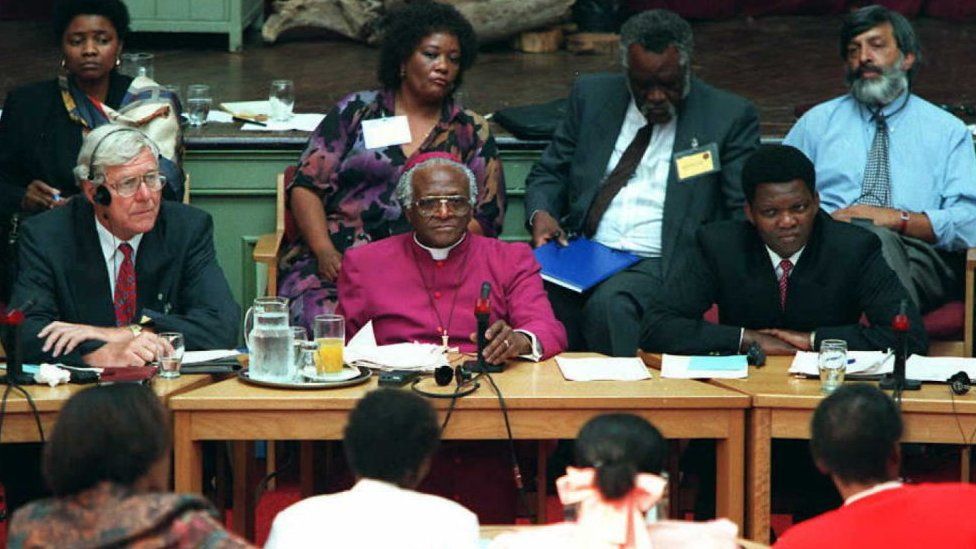

The incident was one of thousands of crimes heard by the TRC to ease South Africa’s delicate transition following the end of apartheid.

President Nelson Mandela asked Archbishop Desmond Tutu to lead the commission, which advocated the healing of the country through reconciliation and forgiveness in order to head off the risk of vengeful violence following the decades of brutality.

It brought together perpetrators, witnesses and victims of human rights violations carried out during the apartheid era to testify in public. The TRC offered the chance of amnesty to those who fully confessed to their crimes, which would at least give relatives the comfort of knowing what had happened to their loved ones.

Six of seven former police officers who confessed their involvement in the killing of the Cradock Four to the TRC were denied amnesty on grounds of not making a full disclosure.

The case was one of about 300 that the TRC referred to the prosecuting authority in 2003 for further investigation and prosecution.

But for relatives who had been waiting decades for justice for their loved ones, what followed was yet more waiting as almost all the cases remained untouched.

It is not entirely clear why the authorities have been dragging their feet.

A possible explanation for the delay came to light in 2015, when the sister of Nokuthula Simelane, a young activist who went missing in 1983, filed a court application for a formal inquest into her disappearance.

The case saw former officials from the prosecuting authority come forward to allege that the government had obstructed the investigation and prosecution of the TRC cases, including that of Ms Simelane.

The claims cited fears that investigations into some cases could lead to calls for the prosecution of members of the governing ANC for their possible involvement in human rights violations during the fight against apartheid.

The BBC approached the South African government for comment, but has not received a reply.

There has been no official inquiry into the claims of political interference and the possible reasons behind it.

However, the news seemed like a vindication to the advocates of victims who had spent years knocking on closed doors. “[It was] finally evidence of what we had long known, we just couldn’t prove it at the time,” says Mr Calata.

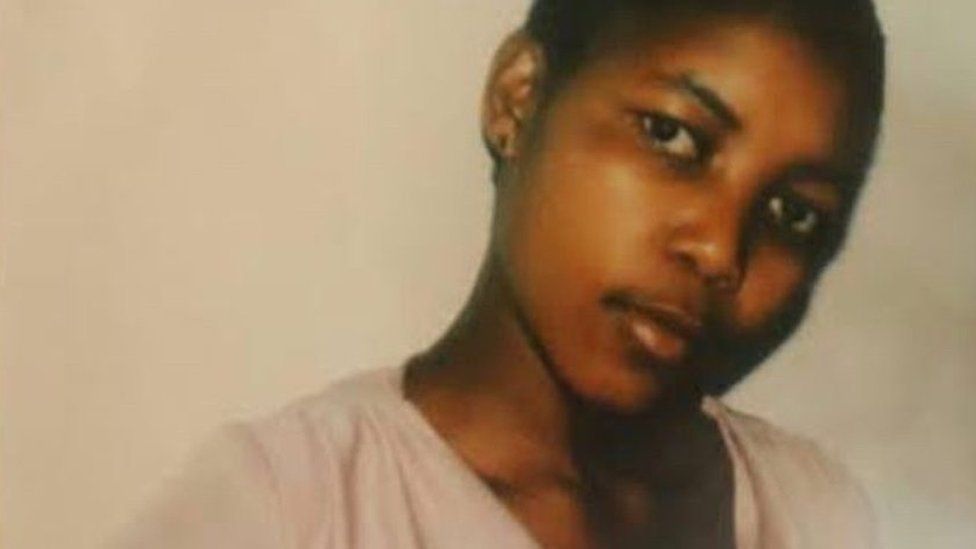

Ms Simelane was a member of uMkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the ANC, when she was abducted in an underground car park in Johannesburg in September 1983 and tortured for weeks, according to testimony given by apartheid-era police officers to the TRC. Her body has never been found.

Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs Thembi Nkadimeng sometimes hopes that she will see her older sister in her dreams. Her memories of Ms Simelane are faded and patchy, but she recalls her love for cooking, how she would lay the table and make her family sit down to the three-course meals that she had prepared.

“I remember my mum saying: ‘You cook but you don’t eat!’ But she loved dessert… at my time it was jelly and custard with peaches and she loved those peaches, she would even eat them out of the tin.”

Ms Nkadimeng regrets that she no longer has the pair of white palazzo trousers that Ms Simelane bought her as a gift for her ninth birthday. Because months later, her sister would go missing, shortly before her own 22nd birthday.

But what pains her most is the heavy toll that time has taken. Two of the four former members of the security police accused of killing her sister have now died. The trial of the remaining two has been beset with delays.

Three of the four officers accused had applied to the TRC for amnesty for the torture of Ms Simelane and were denied. None requested amnesty for her murder.

‘The greatest loss’

The re-opening of an inquest in 2017 into the death of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol in police detention in 1971 was a turning point, says Katarzyna Zdunczyk, TRC programme manager at the South African non-governmental organisation, the Foundation for Human Rights.

A former security branch police officer was charged with Timol’s murder the following year but died before standing trial.

Earlier this year, families of the victims welcomed news that the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) had appointed former TRC commissioner Dumisa Ntsebeza to review its performance in dealing with the apartheid-era cases.

It said that the move built on efforts in recent years to “prevent any undue political influence” in the cases.

But Ms Zdunczyk believes that the inquiry will not be able to look into the full extent of political interference and says that an independent commission of inquiry into the allegations needs to be established.

With many of the perpetrators and key witnesses having now died, the prospects for resolving most of the cases are dim.

But Mr Calata says he will continue to pursue his father’s case. “I can go to his grave, even if it’s 38 years later, to say: ‘Dad now I hope you can finally rest in peace because the people that put you where you are have finally been held accountable.'”

Ms Nkadimeng says that what her family seeks now is closure. Her father and brother died without seeing Ms Simelane buried but she hopes that her mother will.

“I once had a sister. For my mum, she gave birth to a girl who she can’t locate today. She can’t visit her grave, she can’t bury her.”

“I think that’s the greatest loss, that other people may die with their pain.”